I was skeptical about wearing gumboots on an Antarctic Expedition. As my fellow expeditioners trickled down to the ship’s lower deck to board the Zodiac transport boats for our morning excursion, I heard plenty of grumbling gumboot skeptics—so many grumblers, in fact, that the expedition leaders made an announcement to settle the matter.

“Attention Gumboot Grumblers. Trust us, we know what we are doing. Wear your gumboots.”

My inner Canadian was still NOT SOLD on the idea. I had a STERN TALK with myself, reasoning that this was not my home turf and I had absolutely no prior Antarctic experience. I needed to suit up, show up, and follow orders. Wearing two pairs of thick, warm socks, I pulled my expedition-issued gumboots on. All dressed up and ready to go, I climbed into one of the Zodiac boats that was tied by the loading door at the side of the ship.

As the Zodiac boat skimmed over the freezing water, navigating between the chunks of free-floating ice, I hunkered down and nestled myself between two other passengers. The bitter cold wind pummeled me, and the crystalized sleet lacerated the exposed flesh on my face. Mimicking a turtle, I pulled my head into my parka, wrapped my neck scarf around my face, and pinched it all closed air-tight with my gloved hands. I couldn’t see anything, but that was a minor inconvenience compared to the alternative. My gumbooted feet were the least of my concerns.

The driver skillfully maneuvered the Zodiac through the ice, cut the engine, and the boat drifted to shore, the bottom scraping against the gravel, grinding it to a stop. I poked my head out of my pseudo-turtle shell and was astounded by what I saw.

Every visible area of Paulet Island was covered with penguins – a breeding colony of two hundred thousand Adélie penguins and their chicks. At first glance, it looked like the grey cone-shaped slopes of Paulet Island were formed by volcanic rock. However, on closer scrutiny, every slope was a hubbub of activity, teeming with tens of thousands of Adélie penguins!

I could barely take my eyes off the surreal sight when it was my turn to disembark from the Zodiac. Following directions, I swung my legs over the side of the Zodiac, accepted a helping hand, stepped down into the icy water, and waded onto the gravel shore.

Yes, the gumboots came in handy for traipsing through the frosty waters of the Weddell Sea, and my feet did stay dry. However, the verdict was still out on their ability to keep my feet warm.

In the meanwhile, I was MESMERIZED by penguins waddling all around me in every direction. There appeared to be no rhyme or reason for their movement. They were busy, busy, busy, and going every which way. They were CUTE beyond description, hilariously unpredictable, and clumsy.

The top-heavy feisty creatures zipped along at full tilt, tripping over their feet and doing comical face-plants, beak first into the ground. Instantly, they sprang up and beetled off lickety-split in another direction.

While picking my way along the rocky shoreline of Paulet Island, careful to avoid catastrophic collisions with erratic Adélies, I realized there was yet another important purpose for my gumboots.

Penguin guano - penguin poo. That which was not penguin or rock was guano. The wretched stuff was everywhere!

Every year in November, 200,000 Adélie penguins migrate to their breeding grounds on Paulet Island, and they stay there until their young chicks are big enough to survive on their own.

By the beginning of March, the Adélie penguins vacate the 2.25 km² island, leaving nothing behind except their annual deposit of fresh guano. Four months’ worth of fresh guano from approximately 300,000 Adélie penguins.

As winter approaches, the days grow colder, the new guano deposit freezes, and it doesn’t thaw until the following summer when the whole process repeats itself—exactly as it has done for the past 2,900 years. Yes, Paulet Island’s “soil” is comprised of 2,900 years of accumulated penguin guano.

It is prudent to wear gumboots when sloshing around in guano while navigating copious amounts of shoreline rocks and being CHARGED by SCURRYING KAMIKAZE penguins prone to stop abruptly without warning.

If anyone were going to do a head plant in the guano, I would rather it be an Adélie penguin than me.

The island REEKED of PENGUIN POO! The stench permeated everything; it was unavoidable and hung like a lead weight in every molecule of air. It clung to my clothing and hair and splattered across my expedition-issued gum boots. I officially renamed the island “Penguin Poo Island.” I notice the world maps haven’t officially changed the name yet, but these things take time.

The Adélie penguins have some interesting and unique characteristics. Like all penguins, they can’t fly, but they are graceful and stealth swimmers. Playfully frolicking along the surface Antarctic waters at 10 mph, Adélies could easily be mistaken for dolphins. While they are clumsy and awkward on land, they are agile and elegant in the water. Adélies can stay underwater for six minutes and have been known to dive to depths of 575 feet below the surface when foraging for food, although typically, they don’t go much deeper than 165 feet.

Adélies and Emporers are the only two penguin species endemic to Antarctica. The Adélie, one of the smallest of the 18 species of penguins on earth, weighs 4-6 kg (9-13 lbs) and stands 70-73 cm (28-29 inches). These birds have a lot of spunk, personality, and pluck! On average, they migrate between 8,100 to 10,900 miles ANNUALLY to get to their breeding ground on Penguin Poo Island. Their lifespan in the wild is 10 years, and they mate for life.

Mr. Adélie typically arrives on Penguin Poo in October, a few weeks ahead of Mrs. Adélie, so he can build their rock nest and find some fine stone pebbles as part of his mating ritual with his lady. Pebble hunting for the male Adélie is serious business, and the fellas have frequently been observed stealing prized, coveted stones from their neighbors. Every male wants the finest and best for his Mrs. because if she turns her beak up at his offering and rejects it, then there will be no mating that year. In that case, I supposed they’d just go hang around the icebergs for four months.

Mr. Adélie is a very involved father. Typically, Mrs. Adélie will lay two eggs, and both parents take turns egg sitting during the incubation period, 33-35 days. Likewise, Mr. and Mrs. spell each other off while tending to the chicks for the first three weeks. The chicks must be protected from the Antarctic elements and predator birds that are always prepared to swoop down and snatch a nice, tender newborn Adélie penguin for dinner.

The guano in the photo above has a slight reddish tinge, indicating that these penguins have been eating a lot of Antarctic krill. Krill and fish are their food sources.

After three weeks, the chicks are too big to snuggle under the parents for protection, so they are forced out of the nest at that time. The chicks need to grow and gain strength quickly so they can vacate Penguin Poo Island and begin their migration with the rest of the colony at the end of February. Time is short, and it will be survival of the fittest in a race against the onset of colder weather.

The Zodiac drivers pulled the boats to shore, fired up the engines, and kept them running at a slow idle, ready to start transporting expeditioners back to the ship. Having received the cue, people gradually began returning to the loading zone and boarding the Zodiacs.

As much as I was amused by the adorable antics of the penguins, I was ready to get off Penguin Poo Island.

If I NEVER smelled Penguin guano again, it would be perfectly fine with me!

Something captured my attention, and I wanted to take a quick look at it before I went back to the Zodiac. After all, I knew in no uncertain terms this would be my one and only visit to Penguin Poo Island.

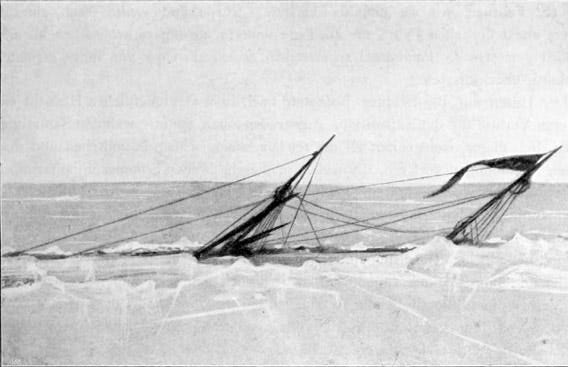

In February 1903, the Swedish ship Antarctic, led by Otto Nordenskjöld and Carl Anton Larsen, was crushed by ice 25 miles from Paulet Island. Five crew members went to get help, and fourteen crew members spent the winter on the island in the stone hut in the photo above. One crew member, a young sailor named Ole Wennesgaard, became ill in June and died—his grave is also part of these rocky ruins.

Looking at the remaining walls of the survivors’ rock hut, I felt an eerie, empty feeling within. The hut was like a voice from the not-so-distant past, reminding me that the land I was visiting was harsh and brutal. Many lives have been lost, and ships have been crushed into mere splinters by the unyielding ice, life-threatening sub-zero temperatures, and hurricane-force winds.

Antarctica is a force to contend with - a powerful force.

Amazing as it was, wearing two pairs of warm socks in my gumboots kept my feet warm. I would NEVER have believed it.

I held onto the ropes along the side of the Zodiac and waded into the Weddell Sea. While standing on one foot at a time, I vigorously swished my muck-plastered gumboots around in the cold water. I ground the rubber soles into the gravel beneath the water to scour all traces of penguin gunk out of the boot treads.

The Zodiac drivers and the Antarctic Dream staff had a very strict policy: Penguin Poo stays on Penguin Poo Island.

Fun adventure, well told! I was reminded of that documentary, March of Penguins, that was popular a while back. The documentary was, among other things, beautiful: good music and narration. But the "Making of" feature that came with the DVD showed the reality of the noise and poo. I think the noise impressed me the most!

Cool adventure - guano and all!