My friend Petra called and invited me to meet her in Dresden, Germany. She had been in Europe for six weeks caring for her elderly mother and needed to take a break. There was no question about my response. Within a matter of days, I was in Germany, open to whatever adventure came my way.

Since we were on her turf, Petra was the designated driver and my personal tour guide. Although she was raised in West Germany, close to the Holland border, her grandparents had lived in East Germany near Dresden. While zipping her small white Opel Corsa car around the busy streets, she shared a fascinating commentary on the sights and history of Dresden.

With a population of 592,000, Dresden is the third largest city in East Germany. It is located along the Elbe River in the State of Saxony, 100 miles (160 km) south of Berlin and just 19 miles (30 km) from the border of the Czech Republic. Historically, Dresden has been revered for its unsurpassed Baroque architecture and numerous collections of priceless art treasures. The city’s beauty was so noteworthy that before WWII, Dresden was known as the “Florence on the Elbe.”

The nights of February 13 & 14, 1945, permanently changed the history of Dresden, Germany. The skies darkened as 1,299 Allied Forces bombers descended over the city, blanketing it with 3,900 tons of bombs and flammable chemicals, leaving behind a death toll of at least 25,000 civilians.

Almost the entire city of Dresden was reduced to a scorching inferno of pulverized sandstone, melted twisted metal, burning smoldering ash, and catastrophic heaps of rubble.

Although WWII ended a few months later, Dresden came under the communist rule of East Germany—most of the city remained minimally restored for the next 45 years.

When the Berlin Wall fell on November 9, 1989, the communist era ended, and East Germany was reunited as one nation with Germany. By 1991, strategies were initiated to help finance the restoration of former East Germany.

Often compared to St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome, the Frauenkirche (Church of Our Lady) had remained a painful scar in the center of Dresden for almost 50 years before plans for its reconstruction began in 1994. The blueprints of Frauenkirche drawn by its original architect in 1726 were used in the project, as well as hundreds of photographs and input from long-time Dresden residents.

The massive rebuilding project required:

13,000 tons of sandstone quarried from the local Elbe Sandstone Mountains and 8,500 sandstone bricks salvaged from the original church

Steel reinforcements

Oakwood for the interior walls and trim

Glass and stained glass windows

Thousands of Happy Free Range Laying Hens

Whoa! Thousands of Happy Free Range Laying Hens?

Yes. An exorbitant number of high-quality chicken eggs were needed to replicate the antique egg-tempera paint for the interior walls of the church.

According to art restoration expert Betsy Porter, free-range chicken hens are HAPPY CHICKENS—they lay the HIGHEST QUALITY eggs, which are preferable for making egg tempera. This durable, long-wearing paint, used by the old master painters prior to the 15th century, is made by mixing the yoke of an egg with color pigment and a small amount of water.

The tempera paint gives the interior walls a slightly iridescent and translucent sheen, with gentle hues of pastel colors that subtly change with the light.

Thank you to all the Happy Free Range Hens for donating an untold number of egg yolks to restore splendor to the interior oak walls of the church.

Well done, Ladies!

The reconstruction of Frauenkirche cost £180 million and took 14 years to complete. Funds were contributed from around the world to restore the church as a symbol of German and International unity, peace, and resilience. On October 30, 2005, Frauenkirche (Church of Our Lady) was officially reconsecrated.

Petra’s Opel Corsa was quite a peppy car with a penchant for exceeding the speed limit. The mini speedmobile promptly got nabbed with two photo radar speeding tickets. The cameras were hidden in the depths of lush green foliage along the roadways, and aside from their instantaneous blinding “gotcha!” flashes, it was impossible to see them. For the record, had I been driving, I would have bagged a few eye-stunning flash tickets as well. The photo radar flash was an equal opportunity speeding ticket dispenser.

Petra squeezed the Opel speedmobile into a parking space along Bautzner Street near the famous Pfund Molkerei (milk shop). We parked legally and didn’t get any photo flashes or parking tickets.

Pfund’s Molkerei is listed in the 1977 Guinness Book of Records as the “Most Beautiful Milk Shop in the World.”

The Pfund Milk Shop has 247.9 m² of hand-painted Villeroy & Boch tiles covering the interior premises that tell the life stories of its founders, Paul and Friedrich Pfund.

The Pfund Brothers combined their resources and bought a small dairy farm in 1879. Dairy farming was a high-risk venture characterized by a high incidence of spoilage and a low demand in the market.

Milk was transported in large metal cans from the dairy farms to the market in the city. After the milk was emptied from the cans at the market, the cans were refilled with city GARBAGE and sent back to the farms for disposal. The dairy farms then washed the soiled milk/garbage cans, and the cycle was repeated.

From a modern perspective, it is obvious why the milk/garbage can combo didn’t fare well for dairy farmers. By the time the milk made it from the farm to market, it was often spoiled or contaminated. And if, by chance, it wasn’t tainted and putrid, it was NOT a hot commodity.

In 1880 Paul Pfund designed a REVOLUTIONARY system for sanitizing the dairy milk industry.

The Pfund Dairy expanded its operations so much that it opened the Pfund Molkerei (milk shop) in 1892 to sell its excess production.

By 1895, the Pfund Molkerei was processing 40,000 liters of milk daily.

Today, the Pfund Molkerei is a fabulous place to buy a nice gift, enjoy a phenomenal lunch, or discover the best-kept secret in Dresden:

CHOCOLATE! MILK CHOCOLATE!

Chocolate is my weakness! I admit, I am a bona fide Chocoholic— the real deal. I LOVE the stuff. It sends my mind swirling and my head spinning. My knees go weak.

Surely, this was a dream, a wishful figment of my imagination. Was Dresden REALLY the BIRTHPLACE of MILK CHOCOLATE? Yes! Yes! I was at Milk Chocolate Ground Zero, hovering above an enclosed glass display case filled with rows and rows of tantalizing, luscious, decadent morsels of chocolate— each one vying for my attention.

My hands trembled, and my lower lip quivered as a stream of DROOL spilled from my mouth and OOZED across the top of the glass showcase.

“Oh no! I’ve slobbered all over the chocolate case!” I considered taking a deft swipe at the condemning puddle with my sleeve, but I wore short sleeves.

Next idea, “I’ll slowly, inconspicuously inch along the case, away from the DROOL POOL, and act like I know nothing about it.”

While I contemplated how to discretely avoid being nailed for slobber-plastering the display case, Frau Frederika Fritz briskly approached the accusatory evidence from the opposite side. Frau Fritz was neatly dressed in a crisp snow-white uniform with “Pfundt Molkerei” embroidered in royal blue on the left pocket of her blouse.

I looked at Frau Fritz, and she looked at me. Eye to eye. I was busted, caught standing right in front of my tell-tale mess. I confess. I did it. It was me.

Frau Frederika Fritz was a real pro! Displaying practiced finesse, she retrieved a hidden washcloth from beneath the counter, and with a few skilled swipes, the glass case was sparkling clean and drool-free. Obviously, I was not the first person to instinctively act like Pavlov’s dog, panting with my tongue hanging out in front of all those chocolates.

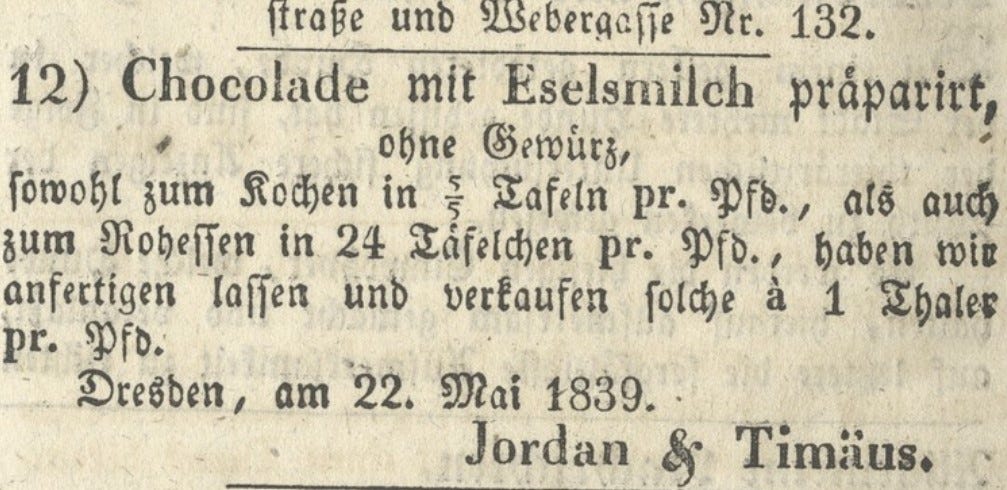

For years, historians attributed the creation of milk chocolate in 1869 to Swiss Chocolatiers Daniel Peter, Henri Nestlé, and Rodolphe Lindt. However, an old archived advertisement discovered by the Dresden Scientist Association in 2007 revealed that Jordan & Timaeus started selling milk chocolate in Dresden, Germany, on May 22, 1839— predating the Swiss development of milk chocolate by at least 30 years.

Since 2007, Gottfried Jordan and August Timaeus have been recognized as the FIRST to make solid milk chocolate. By using steam power, their simple recipe had three ingredients: 60% cocoa, 30% sugar, and 10% donkey milk.

DONKEY MILK?

Jordan & Timaeus used DONKEY MILK in their milk chocolate. Why?

The answer is found in the timeline of history. Jordan & Timaeus launched their Milk Chocolate Debut on May 23, 1839 — Forty years BEFORE Paul Pfund invented the dairy sanitizing system that opened the market for noncontaminated cow’s milk.

In Dresden, throughout the 19th century, donkeys were used extensively as work animals and for their milk. Because donkey milk came straight from the source, it was the preferred choice. It simply made good business sense that, prior to 1880, Jordan & Timaeus used higher quality donkey milk to create their Milk Chocolate.

Those who have duplicated the original Jordan & Timaeus Donkey Milk Chocolate recipe claim it is “grainy, difficult to chew, dark and bitter.” It did not get good reviews. Personally, I’ve never been inclined to sample Donkey Milk Chocolate.

Watch for the next episode of Expect the Unexpected as Petra and I expand our horizons beetling around in the white Opel Speedmobile.

Another beaut!

You can have all the milk chocolate you want.

I want Dark chocolate